Published April 27, 2017 in Episode 71

What are memories but images? And what can images tell us about our story, and about history? Conflict, brutality, and war captured in still images often become the markers of seminal moments in history. The images live on long after the subjects are gone and the events are over. Modern Vietnamese history, in many ways, is still alive — both in the figurative and literal sense. Many of those who lived through the war are still with us, and the deep wounds they carry often remain unhealed, affecting the lives of everyday Vietnamese.

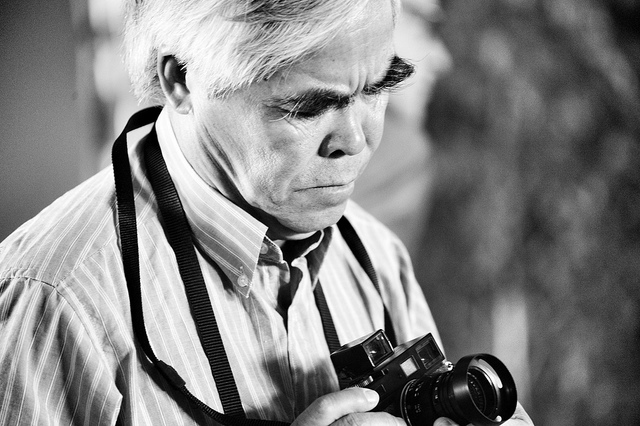

One key purveyor of memory is Nick Út — arguably the most internationally recognized photographer of the Việt Nam war. The Pulitzer-prize winning photojournalist just retired in March after 51 years working for the Associated Press news agency.

Nick Út started working as a photojournalist for the Associated Press at 16 years old. (Photo: Alessio Jacona. CC BY-SA 2.0)

I meet him on the outdoor patio of a phở restaurant in Little Sài Gòn, in Southern California. Út has lived and worked in nearby Los Angeles for over three decades.

Just weeks ago, another legendary photographer, Nguyễn Ngọc Hạnh of the South Vietnamese army, passed away in San Jose, California. Many Vietnamese in the area will be commemorating the Fall of Sài Gòn this week, as the end of the war is known to many here. Others know it to be the Liberation of the South.

I wanted to get Út’s take on the role of photography in shaping news coverage of the war and even how we look at it today. He tells me,

“When they see a newspaper without pictures, they don’t think that article is important. It’s like the photo of Kim Phúc, for example. They see a photo depicting extreme catastrophe, and it makes them want to learn more about her, about the story. If there’s no picture, then people don’t want to read. Pictures are very important.”

The photo he refers to is none other than the so-called Napalm Girl photo — a photo that many credit or blame, depending on whom you ask, to have changed the tide of the Việt Nam war.

The infamous "Napalm Girl" photo. (Photo: Nick Út/AP)

The black and white photo is loud and shocking. When viewing it, we first grapple with the naked, crying young girl in the foreground, her singed skin against the backdrop of napalm smoke. The cries from running villagers in the photo become nearly auditory. Út captured the photo on January 8, 1972, when South Vietnamese planes mistakenly dropped a napalm bomb on Trảng Bàng, a village that had been attacked and occupied by North Vietnamese forces.

The story is one that has been widely featured in media all around the globe — and the photo was the perfect depiction of the horrors of war. Perhaps so perfect, that it was easily used aspropaganda. Út says, “Both the North and the South used the photo of Kim Phúc as propaganda. The North would say, ‘This is a photo of America dropping a bomb to murder the innocent.’ And in the South, “This is a photo of the communists shooting missiles.’ To me, I am telling the truth. And the propagandists, well, they’ll say what they say.”

But Việt Nam war history is complex and riddled with contradictions and controversies —including the history of this war photographer.

Nick Út became a photographer because he was inspired by his brother, an actor-turned-combat photographer, who hated war. His brother and role model, whom he calls anh Bảy, was executed by the Việt Cộng while photographing on their territory. Út later becomes famous for a photo of a young girl nearly burned to death by a bomb dropped by a South Việt Nam plane, taken in a village being overtaken by North Việt Nam forces. Út is revered by many who feel his photo helped lead to America's withdrawal and the war’s end, and resented by others who feel his photo played a key role in helping the North, thus holding a natural bias against the South Việt Nam forces.

Hearing the story of his brother leads me to a photoset I had recently come across — “photos from the winning side” — haunting images that tell stories about the North Việt Nam forces--how they lived, organized, and fought. They are all black and white photos. One depicts Việt Cộng activists in Năm Căn forest, wearing masks to evade capture and interrogation. Another is a Việt Cộng female guerrilla fighter, strapped with a determined stance and an M16 rifle.

When I show them to him, he exclaims that he is familiar with the photos and points out that, while beautifully shot and evocative, the photos are distinct from photojournalism.

Then, in a nearly morbid, matter-of-fact fashion, he tells me that as a photojournalist, after capturing the photos of so many attacked, injured, and dead, he has gained an eye for what a body looks like after a person has just been killed. And when he looks at photos of combat amongst dead soldiers from the war, he can often see that they have been staged. From disturbing images to ones meant to document triumph, he tells me staged photography was common practice.

Another famous photo from the war is the April 30, 1975 photo of a tank rolling through the presidential palace in Sài Gòn. The tricky part of understanding the photo, as well as its presence in history books across the world, is that there were multiple photographers behind variations of the photo with soldiers on a tank, coming through the gates -- a depiction of the North’s victory. He says photographers of the North, who he calls employees of the Vietnamese government, the Communist Party, stood in a different position in documenting these types of moments.

“They work for the Vietnamese government. They have to use propaganda images, but that’s not photojournalism.” He tells me, “The photos have to be staged and re-staged. Like, for example, the photo of the T-54 tank rolling through the gate of the Presidential Palace? That photo is the result of multiple re-staging, that’s how they were able to get that photo. In truth they did not just capture the tank as it rolls into the gate. They had to back up, go out, come back in multiple times so that they could take a beautiful photo.”

Visual image plays a powerful role in helping us understand history, reminding us that different lenses are at play in shaping narratives of the war. Út says narratives are most easily imposed and reinforced when people don’t know what they don’t know. It’s how impressions and interpretations are strengthened.

He says,

“A lot of young people, young Americans, they go to Việt Nam for tourism, they visitthe Củ Chi tunnels, they say ‘Wow! The Việt Cộng are amazing; they built these tunnels all the way into Sài Gòn...’ But I was actually there. I traveled all through the region. B52s dropped bombs every day and those tunnels all collapsed. They were nothing like the way the tunnels are set today.”

In light of an extremely complex war history, perhaps the takeaway is simple: what you see, very possibly, is not what was or what is. Út says that, regardless of one’s field of work, it’s crucial for each person to do their due diligence to understand their medium.

He tells me a story about how he learned the art of photographing baseball,

“Journalists should read a lot of news, watch a lot of news. Just like filmmakers need to watch a lot of films. That’s how you get good. You know in 1977, AP told me to go shoot a baseball game. I was stumped, I thought, what’s baseball? I went to my first baseball game and I thought, what is this? Why does it look like the Việt Cộng running after American soldiers? Why’s everyone running? So I watched all the photographers snapping away, but I came away with nothing. I was frustrated. The next day, I opened a bunch of newspapers and looked at the photos: second base, home plate, home run. This is easy! Then, I was able to shoot just like that.”

It’s safe to say that war is tougher to understand than the game of baseball. And as wars and violence continue to persist in our world, the need to look critically at how the narratives are shaped is just as imperative as it ever has been.